An illumination by Jens Hoffmann

An illumination by Jens Hoffmann

508 Ellis Street, San Francisco, CA 94109

Catalog essay by Jens Hoffmann: Download PDF

As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being.

—Carl Jung

Participating artists include Andrea Bowers, Nina Canell, Adriano Costa, Martin Creed, Claire Fontaine, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Alfredo Jaar, Joseph Kosuth, Tim Lee, Glenn Ligon, Adriana Martinez, Steve McQueen, Jonathan Monk, Paulina Olowska, Mai-Thu Perret, Jason Rhoades, Ana Roldán, Nasser Al Salem, Keith Sonnier, Ron Terada and Cerith Wyn Evans

Ever since the Big Bang created our universe more than ten billion years ago, our Earth has been bathed in light coming from the sun. Light is mentioned in the third verse of the Book of Genesis—the first book of the Hebrew Bible (the Tanakh) and the Christian Old Testament—in which God creates the world and illuminates it by saying, “Let there be light.”

Light, and in particular sunlight, is an essential source of energy and has an incredible effect on how we wander through the world. Every schoolkid knows that thanks to photosynthesis, plants thrive and grow to serve as an essential part of the food chain, not to mention also producing the oxygen we breathe.

Ever since the Greek philosopher Plato proposed his famous allegory of the cave—that the world we see is not the real world, and that philosophers have an obligation to tell the rest of society about authentic existence outside the cave—light has also functioned as a metaphor for education, knowledge, spiritual and intellectual liberation, and hope. We are “illuminated” or “enlightened” with intelligence; light draws us out of “darkness” by puncturing ignorance with bright “rays” of wisdom.

Over the centuries humans have conjured other sources of light. Fire was the earliest, used in the caves of our ancestors as well as in the candles and spirit lamps that were still the main generators of light after dark only one hundred years ago. Today we rely almost exclusively on light powered by electricity, which began with the invention of the incandescent bulb by Thomas Edison and progressed to fluorescent lighting and contemporary light-emitting-diodes, or LEDs.

We have also learned to control light, using it to illuminate our houses and city streets at night, as well as to communicate with one another, as in brightly lit advertising logos, glittering entrance signs to bars and restaurants, and dazzling theater marquees. More practical uses include lighthouses to help boats navigate, Morse code flashes between ships at sea, and the ubiquitous traffic lights around our cities.

One popular source of artificial light, whose heyday came in the mid-twentieth century, is neon. The French scientist, inventor, and engineer Georges Claude is widely considered the father of the neon tube; he was building on the inventions of Heinrich Geissler and other scientist-inventors such as William Crookes, Johann Wilhelm Hittorf, and Daniel McFarlan Moore. In 1910 Claude patented his discovery that neon produces light but (crucially, for its commercial applications) not heat when electricity passes through it. Bright, colorful, bended neon tubes soon began appearing in outdoor advertising of all kinds. One of the first and most celebrated instances was the large sign for the Italian vermouth manufacturer Cinzano, which starting in 1913 illuminated Paris above Boulevard Haussmann with white letters about a yard tall. The first neon signs in the United States arrived from Claude’s company in Los Angeles in 1923: a pair of signs for a Packard car dealership run by the American businessman and industrial pioneer Earle C. Anthony.

“Let There Be (More) Light” features twenty-one artists who use light as a medium, and who look to the early pioneers of neon and fluorescent art for inspiration. There are many connections between light and art. The most direct one is that they both enable enlightenment—one literally, by bringing light into a dark space, and the other intellectually and aesthetically. In “Let There Be (More) Light” the artworks on display are intended do both simultaneously. Indeed, it is difficult not to think of Plato’s allegory of the cave in the context of the exhibition, given the architecture of the gallery space: two tall but small rooms in a cave-like storefront in San Francisco’s bustling Tenderloin neighborhood, a socially and economically heterogeneous zone marked by a distressing and conspicuous collision of concentrated poverty, homelessness, and crime on the one hand and enormous prosperity, wealth, and achievement on the other. The site embodies the contradictory nature of the larger world today in a direct, unidealized, and rather rare manner.

Dan Flavin is probably the best-known artist to work with light in the gallery space. He introduced the concept to the art world in the mid-1960s, in the very early days of Minimalism, when he diagonally mounted an industrially fabricated fluorescent light tube onto a gallery wall. Another forerunner in the use of light as an art material is Robert Irwin, who was associated with the Light and Space movement in California (focusing on the sensory experience of art), and used neon in a less sculptural and more tactile way than Flavin. Other iconic artists who have worked with light include Bruce Nauman and Keith Sonnier. Nauman’s neon works critically examine advertisements and consumer culture, making direct allusions to early commercial neon signs, often with a dark sense of humor. Sonnier has created understated, abstract sculptures with neon lights and other materials such as glass, wire, latex, metal, and even bamboo. He radically reinvented the idea of sculpture in the late 1960s with pieces that, specifically because of his use of neon, can be seen as drawings in space, dialoguing with the architecture surrounding them. Joseph Kosuth is another artist who started using neon early in his career, often in sober and formally restrained ways related to his focus on text and language. He was trying to reduce the work of art to pure communication, information, or ideas, and rejected the traditional notion of the aesthetically elaborate, visually pleasing art object.

Both Sonnier and Kosuth present works as part of “Let There Be (More) Light” alongside a wide range of more recent works by artists from around the globe who all consciously reference the early creators of neon and fluorescent art and continue to pursue their concerns. In their hands, light is a vernacular medium producing bright communications and glowing forms, political manifestations and social critiques. They are renewing popular and critical interest in the history of art made with light and ensuring its continued relevance in the twenty-first century.

Press: C Magazine, KQED Arts

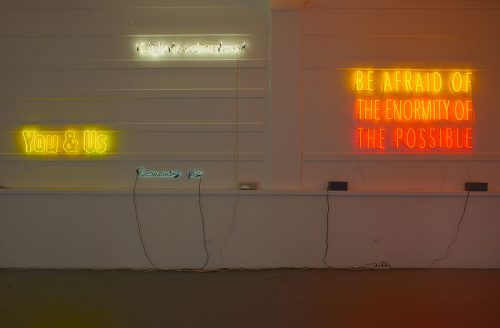

- Installation view

- Installation view

- Installation view

-

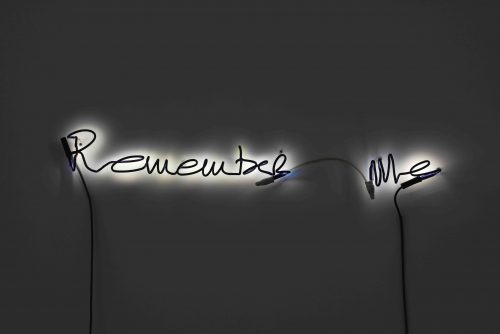

Steve McQueen

Remember Me, 2016

Acrylic paint on neon borosilicate tubes

5 x 39.4 inches / 12.7 x 100 cm

-

Andrea Bowers

Community or Chaos, 2016

Aluminum, cardboard, paint and neon

37 x 48 x 7 inches / 94 x 121.9 x 18 cm

-

Mai-Thu Perret

Uncle Toby (Yellow), 2015

Neon

59.1 x 59.1 x 1.75 inches / 150 x 150 x 4.4 cm

-

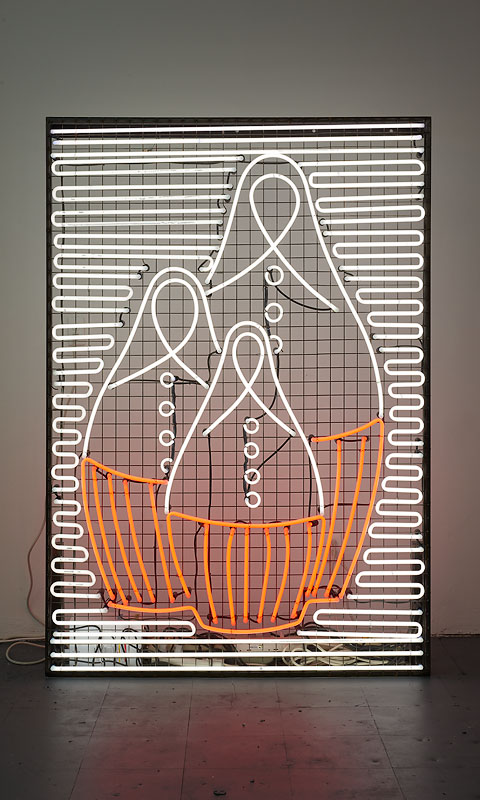

Keith Sonnier

Circle Portal A, 2015

Neon, wire and transformer

80 x 78 x 13 inches / 203.2 x 198.1 x 33 cm

-

Cerith Wyn Evans

Leaning Horizon (neon 6500 Kelvin, 2.1 m) & Leaning Horizon (neon 6800 Kelvin, 2.1 m), 2015

Neon

2 parts, each: height 82.6 inches / 210 cm, diameter 0.5 inches / 1.2 cm

-

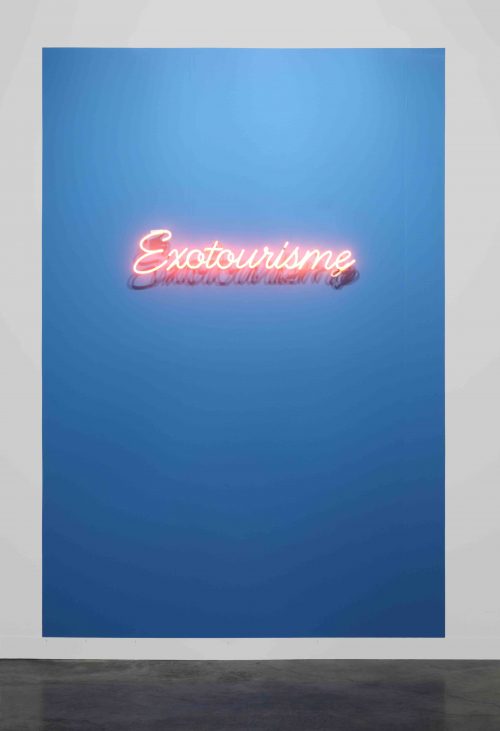

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster

Exotourisme, 2012

Neon, blue paint

7.75 x 40.25 x 2.5 inches / 19.7 x 102.2 x 6.4 cm With wall paint: 118 x 78 3/4 inches / 299.7 x 200 cm

-

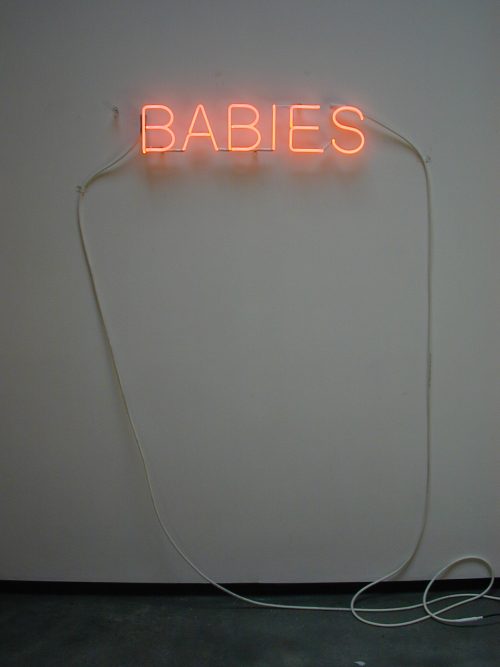

Martin Creed

Work No. 279: BABIES, 2002

Orange neon

Height: 6 inches / 15.2 cm

-

Jason Rhoades

Light, 1997

Plastic bucket, fluorescent tubing, electrical wiring, and fluorescent light fixture

Height: 96 inches / 243.8 cm, width variable

-

Tim Lee

Inert Gas Series/Neon/From A Measured Volume To Indefinite Expansion, Robert Barry, 1969, 2016

Neon

17.25 x 23.5 inches / 43.8 x 59.7 cm

-

Paulina Olowska

Natascha, 2010

White neon

78.74 x 51.18 inches / 200 x 130 cm

-

Jonathan Monk

Fall, 2011

Neon

36 x 78.5 inches / 91.4 x 199.4 cm

-

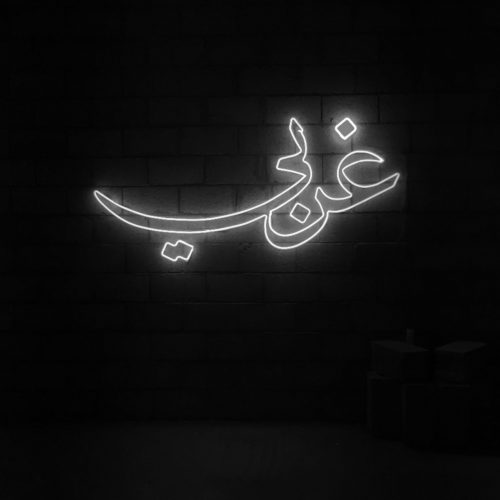

Nasser Al Salem

Arabi, Gharbi (Arabic, Western), 2016

Neon

83.9 x 25.6 inches / 213 x 65 cm

-

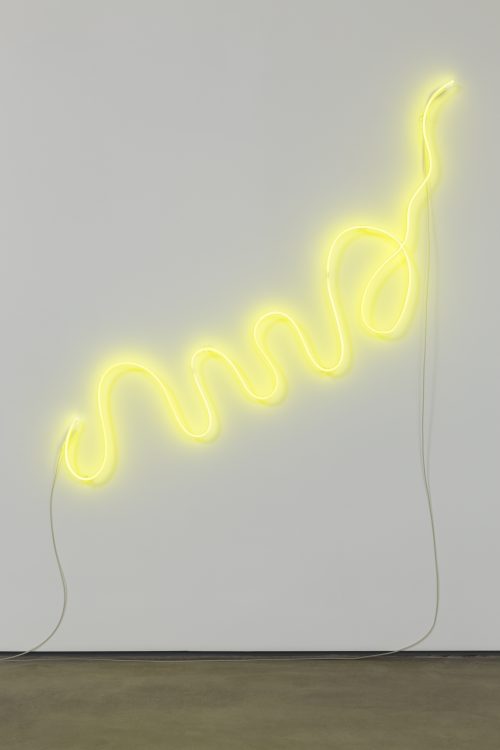

Ana Roldán

Pyramid (yellow), 2011

Neon tube

30.7 x 21.7 inches / 78 x 55 cm, height variable

-

Ron Terada

You & Us, 2006

Neon

13 x 52 inches / 33 x 132 cm

-

Joseph Kosuth

‘R.O.C. No Number #4’, 1991

White neon and transformer

8.5 x 67 x 2 inches / 21.6 x 170.2 x 5.1 cm

-

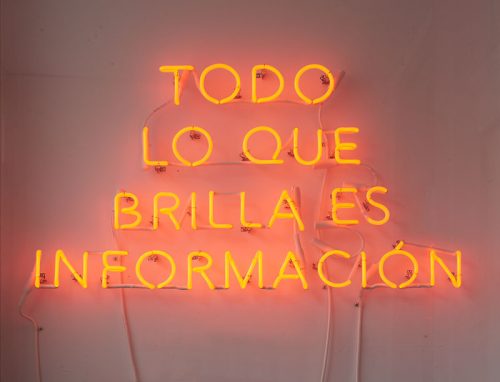

Adriana Martinez

TODO LO QUE BRILLA ES INFORMACION (EVERYTHING THAT SHINES IS INFORMATION), 2016

Neon

22 x 39.4 inches / 56 x 100 cm

-

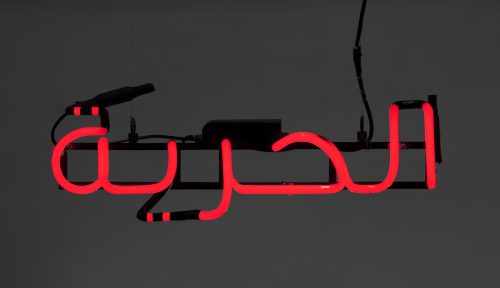

Claire Fontaine

Untitled (Freedom), 2011

Wall, window mounted or suspended neon sign, Ruby red neon 10mm glass (tecnolux no.18), filled with argon/mercury, back-painted, electronic transformer, cables and framework

Approx. 6.7 x 21.25 inches / 17 x 54 cm

-

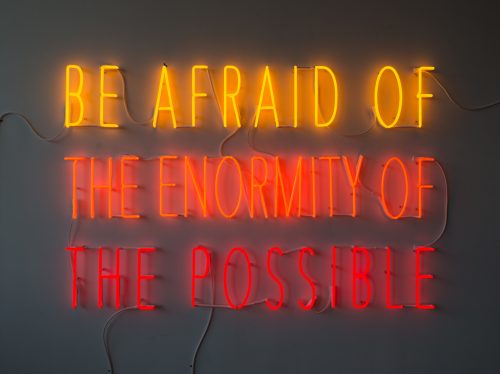

Alfredo Jaar

Be Afraid of the Enormity of the Possible, 2015

Neon

47.5 x 72 inches / 120.7 x 182.9 cm

-

Nina Canell

Yet Another Soft Corner, 2016

Neon, copper, cable, 5000 Volt

1.6 x 27.5 x 35.4 inches / 4 x 70 x 90 cm

Remember Me, 2016

Acrylic paint on neon borosilicate tubes

5 x 39.4 inches / 12.7 x 100 cm

Community or Chaos, 2016

Aluminum, cardboard, paint and neon

37 x 48 x 7 inches / 94 x 121.9 x 18 cm

Uncle Toby (Yellow), 2015

Neon

59.1 x 59.1 x 1.75 inches / 150 x 150 x 4.4 cm

Circle Portal A, 2015

Neon, wire and transformer

80 x 78 x 13 inches / 203.2 x 198.1 x 33 cm

Leaning Horizon (neon 6500 Kelvin, 2.1 m) & Leaning Horizon (neon 6800 Kelvin, 2.1 m), 2015

Neon

2 parts, each: height 82.6 inches / 210 cm, diameter 0.5 inches / 1.2 cm

Exotourisme, 2012

Neon, blue paint

7.75 x 40.25 x 2.5 inches / 19.7 x 102.2 x 6.4 cm With wall paint: 118 x 78 3/4 inches / 299.7 x 200 cm

Work No. 279: BABIES, 2002

Orange neon

Height: 6 inches / 15.2 cm

Light, 1997

Plastic bucket, fluorescent tubing, electrical wiring, and fluorescent light fixture

Height: 96 inches / 243.8 cm, width variable

Inert Gas Series/Neon/From A Measured Volume To Indefinite Expansion, Robert Barry, 1969, 2016

Neon

17.25 x 23.5 inches / 43.8 x 59.7 cm

Natascha, 2010

White neon

78.74 x 51.18 inches / 200 x 130 cm

Fall, 2011

Neon

36 x 78.5 inches / 91.4 x 199.4 cm

Arabi, Gharbi (Arabic, Western), 2016

Neon

83.9 x 25.6 inches / 213 x 65 cm

Pyramid (yellow), 2011

Neon tube

30.7 x 21.7 inches / 78 x 55 cm, height variable

You & Us, 2006

Neon

13 x 52 inches / 33 x 132 cm

‘R.O.C. No Number #4’, 1991

White neon and transformer

8.5 x 67 x 2 inches / 21.6 x 170.2 x 5.1 cm

TODO LO QUE BRILLA ES INFORMACION (EVERYTHING THAT SHINES IS INFORMATION), 2016

Neon

22 x 39.4 inches / 56 x 100 cm

Untitled (Freedom), 2011

Wall, window mounted or suspended neon sign, Ruby red neon 10mm glass (tecnolux no.18), filled with argon/mercury, back-painted, electronic transformer, cables and framework

Approx. 6.7 x 21.25 inches / 17 x 54 cm

Be Afraid of the Enormity of the Possible, 2015

Neon

47.5 x 72 inches / 120.7 x 182.9 cm

Yet Another Soft Corner, 2016

Neon, copper, cable, 5000 Volt

1.6 x 27.5 x 35.4 inches / 4 x 70 x 90 cm